Year: 1985

Publisher: Nintendo

Genre: Sports – Tennis

I believe that, since my childhood, there has been not only a general tendency to make games easier (which is super-good) but also a dumbing down of expectations. Players were once required to control every aspect of the game’s interaction, whereas now there exist a good many games that take parts that would have once fell out of the player’s purview out of their hands. Take, for example, the Nintendo version of Tennis vs. the analogous Wii Sports subgame.

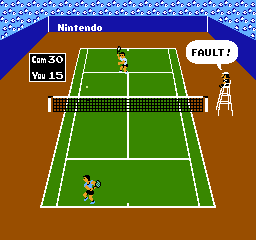

Tennis on the Nintendo plays exactly as one might have once expected a tennis game to play. You control a simulated tennis player who moves around a simulated tennis court and hits a simulated tennis ball. Nothing could be more intuitive: if you want to hit the ball, you move to the ball and hit it. If the ball hits the player rather than the player’s racket, the ball bounces off the player. Furthermore, where you stand in relation to the ball has an intuitive effect on your hits (as does the timing, but that’s a little less obvious and harder to judge and influence). As such, where you stand in relation to the ball is important, just like I imagine it being in real tennis. (Note: The author has never played real tennis.)

In the Wii version, by way of contrast, you control only the swing of the racket (the when and, to some degree, the how). Your little Mii person moves all by themselves, trotting over to the ball and hitting it with a spasm of uncoordinated activity (Note: The author speaks only from personal experience). You aren’t expected to move your Mii on your own, and there is nothing you can do to influence how the Mii moves.

Of course, no control means reduced responsibility. All too often I have been playing the game and seen a ball hit into a spot that my Mii could no hope to reach. “Aha!” I would shout, often aloud in an empty room which isn’t creepy at all, “I didn’t choose to move to that position! If I had been controlling that Mii, it would have never made so grievous a mistake!”

The original Tennis for the Nintendo, however, affords you no such ability to eschew personal responsibility for the outcome. You are fully in control of your little tennis man, and when you make a mistake, Luigi (your referee, or official, or line judge, or umpire, or whatever tennis judges are called) proclaims your failure to the heavens and awards your opponent his requisite points. You controlled every aspect of the game up until this point, so you’ve really no one to blame but yourself.

One feature of this game that does stand out against other games from the Nintendo-hard era is the computer’s distinct lack of cheating. In an early Nintendo game, it’s refreshing to see that the computer is not a cheating bastard. He plays the game fairly and correctly, for what it’s worth, moving at the same speed as you, hitting the ball more or less the same way as you, and even occasionally faulting on serve (especially at lower difficulty levels). Still, despite this refreshing change, the game loses replay value quickly, because, let’s face it, this is Tennis.